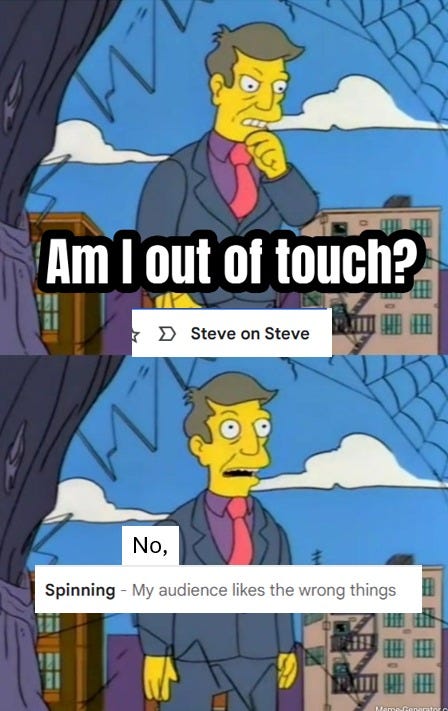

Back in December, I said my audience likes the wrong things. I received some comments, a couple of emails, and a meme (hello, Dan). Evidently, poking people is good.

I promised a reply, so here it is. First, here’s this week’s song. Lyrics at the bottom.

Of course, the meme is both wrong and right. In the manner of the best dialectics, the goal is to be neither Skinner nor kid, out of touch nor cool, but both at once. Bored with what’s popular, excited by possibilities. Sceptical of fashion, enthused by precedent. Mystery is fun, keeps things interesting.2 Otherwise, why bother? It’s kind of like the joy of a good argument: not knowing the answer is the source of the fun. It’s enjoyable to use our human capacities because that’s play, as David Graeber says in this short passage that I think about often.

Inevitably, the mysteries of any field slowly recede as you dig in. Once you peek behind the curtain, you gain new respect for certain practitioners and perhaps lose some reverence for others. Robert Henke once said he thought everyone should get a 30-minute introduction to Ableton so they could get a basic sense for what’s actually interesting, rather than what the software makes easy.3

It’s true that many artists I admire seem to chafe at the affordances of their toolset, have a disdain for the culture surrounding their instrument, are bored by its cliches, or, most important of all, simply want to remain interested in music.

In that sense, Kieran might be right to suggest that I prefer my work which seems less in thrall to “background rules or wtv”. Perhaps those tunes I don’t appreciate as much as my (tiny) audience are those in which I think I played it a little safe. It’s also fun to surprise yourself or make work you’d find interesting if you came across it.

Is cliche a time-tested joy or a fear-driven compromise? More often, the latter. But, as always, it depends on the animating spirit. Spirit and mystery are linked.

That might be one reason I (probably) like my songwriting best, even though it often takes a fairly standard form. The process feels more mercurial, less replicable. It’s true that in great pieces of music, all the parts matter. I’m fond of the expression, “Everything affects everything,” and it’s especially true when it comes to music-making. The tone of the guitar affects the performance, the performance changes the mix-down, the notes of a chord alter the melody, and so on. All the pieces make the whole. But judging from their interviews, even great songwriters don’t really know how they wrote their songs, and readily admit there’s no way they could write the same songs in their old age they did in their youth. There’s something ephemeral to the process, something mysterious. After all, what’s the step-by-step process for writing Autumn Leaves?

On the other hand, digital production itself can be made fairly knowable—it’s often the case that once a process is revealed, anyone can follow the steps and produce an identical result. In a way, that removes some of the mystery.

That’s also true, to an extent, of many kinds of technical virtuosity. The dedication required to be a shred guitarist rapidly sweep-picking arpeggios is very impressive, but there’s also a recipe: set the metronome slow, repeat, speed up, repeat, etc. Eventually, you’ll get it. That method doesn’t necessarily rot the fruits of their labour — I can’t play very fast — but it makes the harvest less mysterious. If one isn’t careful, the accomplishment of great technique can be a kind of pyrrhic victory. If the victory becomes the destination, you might forget why you started in the first place.

I thought of this dichotomy between mystery and repeatability this week while listening to Metallica’s ...And Justice for All, suggested to me by the 1001 Albums Generator.4

In the album, as Simon Reynolds said in a contemporaneous review, “Everything depends on utter punctuality and supreme surgical finesse. It’s probably the most incisive music [he’d] ever heard, in the literal sense of the word”.

Yet it struck me that in the 21st century, the music sounds homespun, kind of quaint. I’ve noticed similar things before when listening to bands like Iron Maiden: “This is it? These cutesey guitars?”

Perhaps the technical aspects of an art form will inevitably be demystified. If the music is defined by speed and precision, faster and more precise players will emerge. If it’s defined by sound processing techniques — those that make guitars sound heavier or drums feel punchier — engineers will come along with newer techniques that make the music heavier and punchier.

Which means the mystery lies in the spirit of the adventurous sparks who concocted the recipe.

Spirit and mystery are linked.

A lot of the most idiosyncratic work is made when people are at the edge of their abilities, when they don’t quite know what they’re doing. Unable to fully rely on experience, curiosity and perception come to the fore. You have to think and feel for yourself. Intuition can be a more reliable guide in these circumstances than tradition. Doing your best with what you have.

James Holden once said something like, “If something is easier to do, it has less value.” I don't fully agree, but openness, curiosity, and challenge often go hand in hand with spirit. By trying to go beyond (yourself or the beaten path), it’s more likely you also tap into your spirit, because you have to trust your own intuition, perception, and curiosity. Those with a natural, gut-trusting confidence might be able to access that right away, while others have to spend years slowly chipping away at the twin edifices of fear and influence to let their spirits shine.

Perhaps this is just a long-winded way of saying I get bored easily and that I don’t have the urge to single-discipline mastery. ‘Focus on your strengths,’ the careerist saying goes. How boring.5 Hardly “hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner…without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic.”

I think it’s good for artists to be a bit contrarian. In an era obsessed with clicks, ‘monthly listeners’ (truly the most banal metric), and professionalism, idiosyncrasy and spirit are more important than ever.6

Nurture your Spirit. Investigate the Mysteries. We need that more than we need more sick bangers m8.

A sensitive soul has many pitfalls,

Misses his momma but he never calls,

Love is sweet but pain is better,

So love his sheets and kiss him better.

Booted toes and worn out clothes,

To match the texture of his prose.

Loves to chat to the pretty girls,

Face to face on their pillows.

So many books in so little time?

Nah, Wikipedia plus a little wine.

Works part time to get undressed,

And that new Taylor Swift? Obsessed.

How many hours, how many weeks?

I call it the “look, no hands!” technique.

I’m in love! Oo oh oo oh oo oh!

I’m in love! Oo oh oo oh oo oh!

With a ma-an who loves his words!

With a man who shares them with the world

Breaks a sweat when he’s out smoking,

Wears a tuque when it’s not snowing,

I heard he keeps his feelings there,

Between his tea-tree shampooed hairs.

Activist author singer swimmer,

No more Facebook, he’s a winner.

Tries to be a ‘lil less shitty,

By calling all your pussies pretty.

Breaks new ground for an hour a day,

To ward away his sense of shame.

Namedrops at dinner with distinction,

Hey! You’d be the right sort of girl downtown.

You’d be the right sort of girl downtown.

You’d be the right sort of girl downtown.

You’d be the right sort of girl downtown.

I’m in love! Oo oh oo oh oo oh!

I’m in love! Oo oh oo oh oo oh!

I love a ma-an who loves his words!

A man who shares his with the world.

I’m in love oo oh oo oh oo oh

I’m in love oo oh oo oh oo oh

I’m love

Will tear down sweeping generalizations for sex,

Will hold forth upon a topic of complexity as long as you’re impressed.

Will expound any rational argument, condensed or finessed,

Fuck, okay, for sure, if you’ll just take off that dress.

Smell the garlic on my breath and then you’ll know me.

Hold me face to face and waist to waist so you can show me.

Smell the garlic on my breath and then you’ll know me.

Hold me face to face and waist to waist so you can show me.

Hey! I’ll love you even if you lie.

I’ll love you even if you lie.

I’ll love you even if you lie.

I’ll love you even if you lie.

Even if you lie.

Even if you lie.

Even if you lie.

There’s a version of this tune with a short spoken word bit at the start that select die-hards might get to hear someday.

This morning, I read Pitchfork's review of Hejira, and these lines jumped out at me:

"At the end of the ’70s, Mitchell told Rolling Stone it was never her goal to be the queen of her generation, or the best. Her goal was to remain interested in music."

“Here’s the thing,” Mitchell told Rolling Stone in 1979. “You can stay the same and protect the formula that gave you your initial success. They’re going to crucify you for staying the same. If you change, they’re going to crucify you for changing. But staying the same is boring. And change is interesting. So of the two options, I’d rather be crucified for changing.”

As a founder of Ableton (though not currently especially active in its development), Henke is something of an interested party, but I think his point stands.

So far, the suggestions have skewed heavily toward white male rock bands from the second half of the twentieth century. The Beatles, the Doors, Oasis, Supertramp, and so on. Not really my wheelhouse, but that’s made it fairly generative. The Doors’ self-titled debut turns out to be great. Freaky circus music with squelchy, gooey bass tones. And the Beatles were not that great until they stopped touring. (Perhaps they started feeding their spirits instead of feeding the masses…)

Which is better: the perfect, towering accomplishment or the curious collection of idiosyncratic explorations?

Are you, or were your formerly, the right sort of girl downtown? Have you been personally victimized by the man in this song? You may be entitled to financial compensation!